In a first, Russia's APT28 hacking group appears to have remotely breached the Wi-Fi of an espionage target by hijacking a laptop in another building across the street.

Photo Illustration: WIRED Staff; Getty Images

For determined hackers, sitting in a car outside a target's building and using radio equipment to breach its Wi-Fi network has long been an effective but risky technique. These risks became all too clear when spies working for Russia's GRU military intelligence agency were caught red-handed on a city street in the Netherlands in 2018 using an antenna hidden in their car's trunk to try to hack into the Wi-Fi of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

Since that incident, however, that same unit of Russian military hackers appears to have developed a new and far safer Wi-Fi hacking technique: Instead of venturing into radio range of their target, they found another vulnerable network in a building across the street, remotely hacked into a laptop in that neighboring building, and used that computer's antenna to break into the Wi-Fi network of their intended victim—a radio-hacking trick that never even required leaving Russian soil.

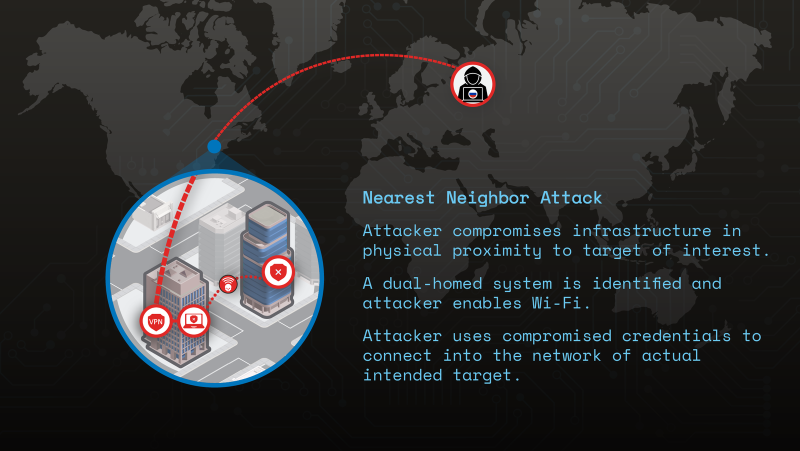

At the Cyberwarcon security conference in Arlington, Virginia, today, cybersecurity researcher Steven Adair will reveal how his firm, Volexity, discovered that unprecedented Wi-Fi hacking technique—what the firm is calling a “nearest neighbor attack"—while investigating a network breach targeting a customer in Washington, DC, in 2022. Volexity, which declined to name its DC customer, has since tied the breach to the Russian hacker group known as Fancy Bear, APT28, or Unit 26165. Part of Russia's GRU military intelligence agency, the group has been involved in notorious cases ranging from the breach of the Democratic National Committee in 2016 to the botched Wi-Fi hacking operation in which four of its members were arrested in the Netherlands in 2018.

In this newly revealed case from early 2022, Volexity ultimately discovered not only that the Russian hackers had jumped to the target network via Wi-Fi from a different compromised network across the street, but also that this prior breach had also potentially been carried out over Wi-Fi from yet another network in the same building—a kind of “daisy-chaining” of network breaches via Wi-Fi, as Adair describes it.

“This is the first case we’ve worked where you have an attacker that’s extremely far away and essentially broke into other organizations in the US in physical proximity to the intended target, then pivoted over Wi-Fi to get into the target network across the street,” says Adair. “That’s a really interesting attack vector that we haven’t seen before.”

A slide describing the “nearest neighbor attack” that Russian hackers used to breach a DC network via Wi-Fi, from the Cyberwarcon presentation of Volexity founder Steven Adair.

Illustration: Volexity

Based on the hackers' targeting of individuals within their customer's network, Adair says that the GRU hackers appear to have been seeking intelligence about Ukraine. It's no coincidence, he says, that the daisy-chained Wi-Fi-based intrusion was carried out in the months just before and after Russia's initial full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Adair argues, though, that the case should serve as a broader warning about cybersecurity threats to Wi-Fi for high-value targets—and not just from the usual suspects loitering in the parking lot or the lobby. “Now we know that a motivated nation-state is doing this and has done it,” says Adair, “It puts on the radar that Wi-Fi security has to be ramped up a good bit.” He suggests organizations that might be the target of similar remote Wi-Fi attacks consider limiting the range of their Wi-Fi, changing the network's name to make it less obvious to potential intruders, or introducing other authentication security measures to limit access to employees.

Adair says that Volexity first began investigating the breach of its DC customer's network in the first months of 2022, when the company saw signs of repeated intrusions into the customer's systems by hackers who had carefully covered their tracks. Volexity's analysts eventually traced the compromise to a hijacked user's account connecting to a Wi-Fi access point in a far end of the building, in a conference room with external-facing windows. Adair says he personally scoured the area looking for the source of that connection. “I went there to physically run down what it could be. We looked at smart TVs, looked for devices in closets. Is someone in the parking lot? Is it a printer?” he says. “We came up dry.”

Only after the next intrusion, when Volexity managed to get more complete logs of the hackers' traffic, did its analysts solve the mystery: The company found that the hijacked machine which the hackers were using to dig around in its customer's systems was leaking the name of the domain on which it was hosted—in fact, the name of another organization just across the road. “At that point, it was 100 percent clear where it was coming from,” Adair says. “It's not a car in the street. It's the building next door.”

With the cooperation of that neighbor, Volexity investigated that second organization's network and found that a certain laptop was the source of the street-jumping Wi-Fi intrusion. The hackers had penetrated that device, which was plugged into a dock connected to the local network via Ethernet, and then switched on its Wi-Fi, allowing it to act as a radio-based relay into the target network. Volexity found that, to break into that target's Wi-Fi, the hackers had used credentials they'd somehow obtained online but had apparently been unable to exploit elsewhere, likely due to two-factor authentication.

Volexity eventually tracked the hackers on that second network to two possible points of intrusion. The hackers appeared to have compromised a VPN appliance owned by the other organization. But they had also broken into the organization's Wi-Fi from another network's devices in the same building, suggesting that the hackers may have daisy-chained as many as three networks via Wi-Fi to reach their final target. “Who knows how many devices or networks they compromised and were doing this on,” says Adair.

In fact, even after Volexity evicted the hackers from their customer's network, the hackers tried again that spring to break in via Wi-Fi, this time attempting to access resources that were shared on the guest Wi-Fi network. “These guys were super persistent,” says Adair. He says that Volexity was able to detect this next breach attempt, however, and quickly lock out the intruders.

Volexity had presumed early on in its investigation that the hackers were Russian in origin due to their targeting of individual staffers at the customer organization focused on Ukraine. Then in April, fully two years after the original intrusion, Microsoft warned of a vulnerability in Windows' print spooler that had been used by Russia's APT28 hacker group—Microsoft refers to the group as Forest Blizzard—to gain administrative privileges on target machines. Remnants left behind on the very first computer Volexity had analyzed in the Wi-Fi-based breach of its customer exactly matched that technique. “It was an exact one-to-one match,” Adair says.

The notion that APT28 would be behind the daisy-chained Wi-Fi hacking makes sense, says John Hultquist, the founder of Cyberwarcon who also leads threat intelligence at Google-owned cybersecurity firm Mandiant and has long tracked the GRU hackers. He sees the technique Volexity uncovered as the natural evolution of APT28's “close-access” hacking methods, in which the GRU has sent small traveling teams in person to hack into target networks via Wi-Fi if other methods failed.

“This is essentially a close-access op like they’ve done in the past, but without the close access,” Hultquist says.

The switch to hacking via Wi-Fi from a remotely compromised device rather than physically placing a spy nearby represents a logical next step following the GRU's operational security disaster in 2018, when its hackers were caught in a car in The Hague attempting to hack the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons in response to the OPCW's investigation of the attempted assassination of GRU defector Sergei Skripal. In that incident, the APT28 team was arrested and their devices were seized, revealing their travel around the world from Brazil to Malaysia to carry out similar close-access attacks.

“If a target is important enough, they’re willing to send people in person. But you don’t have to do that if you can come up with an alternative like what we’re seeing here,” Hultquist says. “This is potentially a major improvement for those operations, and it’s something we’ll probably see more of—if we haven’t already.”